The supervisor establishes capital adequacy requirements for solvency purposes so that insurers can absorb significant unforeseen losses and to provide for degrees of supervisory intervention.

This ICP does not directly apply to non-insurance entities (regulated or unregulated) within an insurance group, but it does apply to insurance legal entities and insurance groups with regard to the risks posed to them by non-insurance entities.

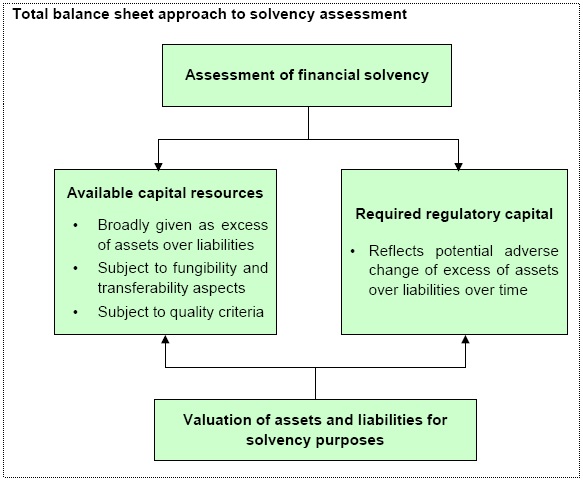

The supervisor requires that a total balance sheet approach is used in the assessment of solvency to recognise the interdependence between assets, liabilities, regulatory capital requirements and capital resources and to require that risks are appropriately recognised.

The overall financial position of an insurer should be based on consistent measurement of assets and liabilities and explicit identification and consistent measurement of risks and their potential impact on all components of the balance sheet. In this context, the IAIS uses the term total balance sheet approach to refer to the recognition of the interdependence between assets, liabilities, regulatory capital requirements and capital resources. A total balance sheet approach should also require that the impacts of relevant material risks on an insurer’s overall financial position are appropriately and adequately recognised [6].

[6] It is noted that the total balance sheet approach is an overall concept rather than implying use of a particular methodology.

The assessment of the financial position of an insurer for supervision purposes addresses the insurer’s technical provisions, required capital and available capital resources. These aspects of solvency assessment (namely technical provisions and capital) are intrinsically inter-related and cannot be considered in isolation by a supervisor.

Technical provisions and capital have distinct roles, requiring a clear and consistent definition of both elements. Technical provisions represent the amount that an insurer requires to fulfil its insurance obligations and settle all commitments to policyholders and other beneficiaries arising over the lifetime of the portfolio [7]. In this ICP, the term regulatory capital requirements refers to financial requirements that are set by the supervisor and relates to the determination of amounts of capital that an insurer must have in addition to its technical provisions.

[7] This includes costs of settling all commitments to policyholders and other beneficiaries arising over the lifetime of the portfolio of policies, the expenses of administering the policies, the costs of hedging, reinsurance, and of the capital required to cover the remaining risks.

Technical provisions and regulatory capital requirements should be covered by adequate and appropriate assets, having regard to the nature and quality of those assets. To allow for the quality of assets, supervisors may consider applying restrictions or adjustments (such as quantitative limits, asset eligibility criteria or “prudential filters”) where the risks inherent in certain asset classes are not adequately covered by the regulatory capital requirements.

Capital resources may be regarded very broadly as the amount of the assets in excess of the amount of the liabilities. Liabilities in this context includes technical provisions and other liabilities (to the extent these other liabilities are not treated as capital resources – for example, liabilities such as subordinated debt may under certain circumstances be given credit for regulatory purposes as capital – see Guidance 17.10.8 – 17.10.11). Assets and liabilities in this context may include contingent assets and contingent liabilities.

The capital adequacy assessment of an insurance legal entity which is a member of an insurance group needs to consider the value of any holdings the insurance legal entity has in affiliates. Consideration may be given, either at the level of the insurance legal entity or the insurance group, to the risks attached to this value.

Where the value of holdings in affiliates is included in the capital adequacy assessment and the insurance legal entity is the parent of the group, group-wide capital adequacy assessment and legal entity assessment of the parent may be similar in outcome although the detail of the approach may be different. For example, a group-wide assessment may consolidate the business of the parent and its subsidiaries and assess the capital adequacy for the combined business while a legal entity assessment of the parent may consider its own business and its investments in its subsidiaries.

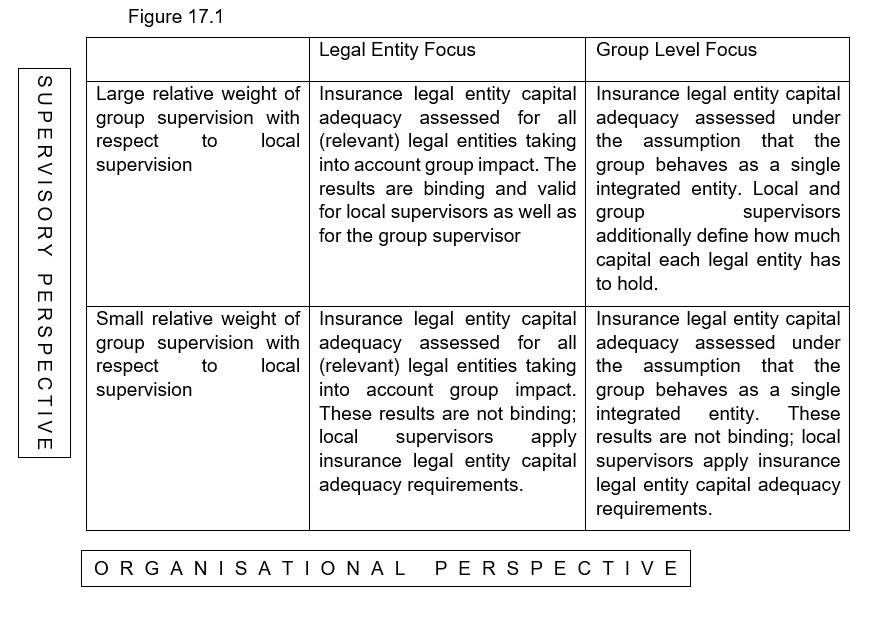

- group level focus; and

- legal entity focus.

The choice of approach would depend on the preconditions in a jurisdiction, the legal environment which may specify the level at which the group-wide capital requirements are set, the structure of the group and the structure of the supervisory arrangements between the supervisors.

Under a group-wide capital adequacy assessment which takes a group level focus, the insurance group is considered primarily as a single integrated entity for which a separate assessment is made for the group as a whole on a consistent basis, including adjustments to reflect constraints on the fungibility of capital and transferability of assets among group members. Hence under this approach, a total balance sheet approach to solvency assessment is followed which is (implicitly or explicitly) based on the balance sheet of the insurance group as a whole. However, adjustments may be necessary appropriately to take into account risks from non-insurance members of the insurance group, including cross-sector regulated entities and non-regulated entities.

Methods used for approaches with a group level focus may vary in the way in which group capital requirements are calculated. Either the group’s consolidated accounts may be used as a basis or an aggregation method may be used. The former is already adjusted for intra-group holdings and further adjustments may then need to be made to reflect the fact that the group may not behave or be allowed to behave as one single entity [9]. This is particularly the case in stressed conditions. The latter method may sum surpluses or deficits (ie the difference between capital resources and capital requirements) for each insurance legal entity in the group with relevant adjustments for intra-group holdings in order to measure an overall surplus or deficit at group level. Alternatively, it may sum the insurance legal entity capital requirements and insurance legal entity capital resources separately in order to measure a group capital requirement and group capital resources. Where an aggregation approach is used for a cross-border insurance group, consideration should be given to consistency of valuation and capital adequacy requirements and of their treatment of intra-group transactions.

[9]Consolidated accounts may be those used for accounting purposes or may differ (eg in terms of the entities included in the consolidation).

Under a group-wide capital adequacy assessment which takes a legal entity focus, the insurance group is considered primarily as a set of interdependent legal entities. The focus is on the capital adequacy of each of the parent and the other insurance legal entities in the insurance group, taking into account risks arising from relationships within the group, including those involving non-insurance members of the group. The regulatory capital requirements and resources of the insurance legal entities in the group form a set of connected results but no overall regulatory group capital requirement is used for regulatory purposes. This is still consistent with a total balance sheet approach, but considers the balance sheets of the individual group entities simultaneously rather than amalgamating them to a single balance sheet for the group as a whole. Methods used for approaches with a legal entity focus may vary in the extent to which there is a common basis for the solvency assessment for all group members and the associated communication and coordination needed among supervisors.

For insurance legal entities that are members of groups and for insurance sub-groups that are part of a wider insurance or other sector group, the additional reasonably foreseeable and relevant material risks arising from being a part of the group should be taken into account in capital adequacy assessment.

The supervisor establishes regulatory capital requirements at a sufficient level so that, in adversity, an insurer’s obligations to policyholders will continue to be met as they fall due and requires that insurers maintain capital resources to meet the regulatory capital requirements.

An insurer's Board and Senior Management have the responsibility to ensure that the insurer has adequate and appropriate capital to support the risks it undertakes. Capital serves to reduce the likelihood of failure due to significantly adverse losses incurred by the insurer over a defined period, including decreases in the value of the assets and/or increases in the obligations of the insurer, and to reduce the magnitude of losses to policyholders in the event that the insurer fails.

From a regulatory perspective, the purpose of capital is to ensure that, in adversity, an insurer’s obligations to policyholders will continue to be met as they fall due. Regulators should establish regulatory capital requirements at the level necessary to support this objective.

In the context of its own risk and solvency assessment (ORSA), the insurer would generally be expected to consider its financial position from a going concern perspective (that is, assuming that it will carry on its business as a going concern and continue to take on new business) but may also need to consider a run-off and/or winding-up perspective (eg where the insurer is in financial difficulty). The determination of regulatory capital requirements may also have aspects of both a going concern and a run-off[10] or winding-up perspective. In establishing regulatory capital requirements, therefore, supervisors should consider the financial position of insurers under different scenarios of operation.

[10] In this context, “run-off” refers to insurers that are still solvent but have closed to new business and are expected to remain closed to new business.

From a macro-economic perspective, requiring insurers to maintain adequate and appropriate capital enhances the safety and soundness of the insurance sector and the financial system as a whole, while not increasing the cost of insurance to a level that is beyond its economic value to policyholders or unduly inhibiting an insurer’s ability to compete in the marketplace. There is a balance to be struck between the level of risk that policyholder obligations will not be paid with the cost to policyholders of increased premiums to cover the costs of servicing additional capital.

The level of capital resources that insurers need to maintain for regulatory purposes is determined by the regulatory capital requirements specified by the supervisor. A deficit of capital resources relative to capital requirements determines the additional amount of capital that is required for regulatory purposes.

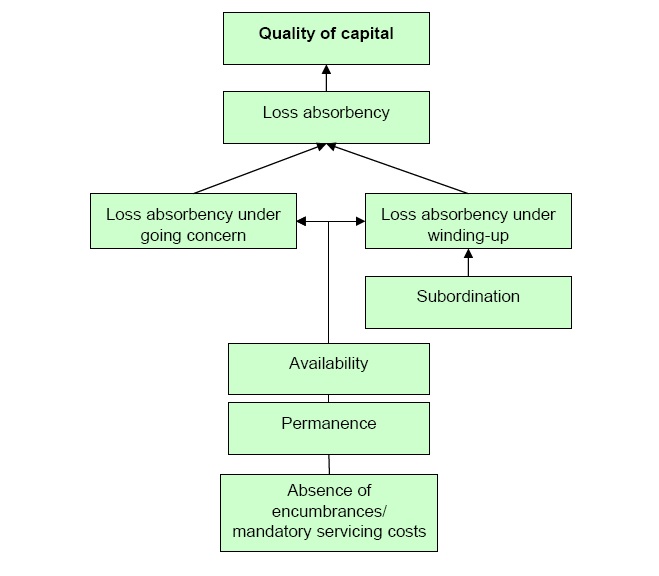

- reduce the probability of insolvency by absorbing losses on a going concern basis or in run-off; and/or

- reduce the loss to policyholders in the event of insolvency or winding-up.

The extent to which elements of capital achieve the above outcomes will vary depending on their characteristics or “quality”. For example, ordinary share capital may be viewed as achieving both of the above, whereas subordinated debt may be viewed largely as only protecting policyholders in insolvency. Capital which achieves both of the above is sometimes termed “going concern capital” and capital which only reduces the loss to policyholders in insolvency is sometimes termed “wind-up capital” or “gone concern” capital. It would be expected that the former (ie going concern capital instruments) should form the substantial part of capital resources.

For an insurer, the management and allocation of capital resources is a fundamental part of its business planning and strategies. In this context, capital resources typically serve a broader range of objectives than those in Guidance 17.2.6. For example, an insurer may use capital resources over and above the regulatory capital requirements to support future growth or to achieve a targeted credit rating.

It is noted that an insurer’s capital management (in relation to regulatory requirements and own capital needs) should be supported and underpinned by establishing and maintaining a sound enterprise risk management framework, including appropriate risk and capital management policies, practices and procedures which are applied consistently across its organisation and are embedded in its processes. Maintaining sufficient capital resources alone is not sufficient protection for policyholders in the absence of disciplined and effective risk management policies and processes (see ICP 16 Enterprise Risk Management for Solvency Purposes).

The supervisor should require insurance groups to maintain capital resources to meet regulatory capital requirements. These requirements should take into account the non-insurance activities of the insurance group. For supervisors that undertake group-wide capital adequacy assessments with a group level focus this means maintaining insurance group capital resources to meet insurance group capital requirements for the group as a whole. For supervisors that undertake group-wide capital adequacy assessments with a legal entity focus this means maintaining capital resources in each insurance legal entity based on a set of connected regulatory capital requirements for the group’s insurance legal entities which fully take the relationships and interactions between these legal entities and other entities in the insurance group into account.

It is not the purpose of group-wide capital adequacy assessment to replace assessment of the capital adequacy of the individual insurance legal entities in an insurance group. Its purpose is to require that group risks are appropriately allowed for and the capital adequacy of individual insurers is not overstated, eg as a result of multiple gearing and leverage of the quality of capital or as a result of risks emanating from the wider group, and that the overall impact of intra-group transactions is appropriately assessed.

Group-wide capital adequacy assessment considers whether the amount and quality of capital resources relative to required capital is adequate and appropriate in the context of the balance of risks and opportunities that group membership brings to the group as a whole and to insurance legal entities which are members of the group. The assessment should satisfy requirements relating to the structure of group-wide regulatory capital requirements and eligible capital resources and should supplement the individual capital adequacy assessments of insurance legal entities in the group. It should indicate whether there are sufficient capital resources available in the group so that, in adversity, obligations to policyholders will continue to be met as they fall due. If the assessment concludes that capital resources are inadequate or inappropriate then corrective action may be triggered either at a group (eg authorised holding or parent company level) or an insurance legal entity level.

The quantitative assessment of group-wide capital adequacy is one of a number of tools available to supervisors for group-wide supervision. If the overall financial position of a group weakens it may create stress for its members either directly through financial contagion and/or organisational effects or indirectly through reputational effects. Group-wide capital adequacy assessment should be used together with other supervisory tools, including in particular the capital adequacy assessment of insurance legal entities in the group. A distinction should be drawn between regulated entities (insurance and other sector) and non-regulated entities. It is necessary to understand the financial positions of both types of entities and their implications for the capital adequacy of the insurance group but this does not necessarily imply setting regulatory capital requirements for non-regulated entities. In addition, supervisors should have regard to the complexity of intra-group relationships (between both regulated and non-regulated entities), contingent assets and liabilities and the overall quality of risk management in assessing whether the overall level of safety required by the supervisor is being achieved.

For insurance legal entities that are members of groups and for insurance sub-groups that are part of a wider insurance or other sector group, capital requirements and capital resources should take into account all additional reasonably foreseeable and relevant material risks arising from being a part of any of the groups.

The regulatory capital requirements include solvency control levels which trigger different degrees of intervention by the supervisor with an appropriate degree of urgency and requires coherence between the solvency control levels established and the associated corrective action that may be at the disposal of the insurer and/or the supervisor.

The supervisor should establish control levels that trigger intervention by the supervisor in an insurer’s affairs when capital resources fall below these control levels. The control level may be supported by a specific framework or by a more general framework providing the supervisor latitude of action. A supervisor’s goal in establishing control levels is to safeguard policyholders from loss due to an insurer’s inability to meet its obligations when due.

The solvency control levels provide triggers for action by the insurer and supervisor. Hence they should be set at a level that allows intervention at a sufficiently early stage in an insurer’s difficulties so that there would be a realistic prospect for the situation to be rectified in a timely manner with an appropriate degree of urgency. At the same time, the reasonableness of the control levels should be examined in relation to the nature of the corrective measures. The risk tolerance of the supervisor will influence both the level at which the solvency control levels are set and the intervention actions that are triggered.

When establishing solvency control levels it is recognised that views about the level that is acceptable may differ from jurisdiction to jurisdiction and by types of business written and will reflect, amongst other things, the extent to which the pre-conditions for effective supervision exist within the jurisdiction and the risk tolerance of the particular supervisor. The IAIS recognises that jurisdictions will acknowledge that a certain level of insolvencies may be unavoidable and that establishing an acceptable threshold may facilitate a competitive marketplace for insurers and avoid inappropriate barriers to market entry.

The criteria used by the supervisor to establish solvency control levels should be transparent. This is particularly important where legal action may be taken in response to an insurer violating a control level. In this case, control levels should generally be simple and readily explainable to a court when seeking enforcement of supervisory action.

Supervisors may need to consider different solvency control levels for different modes of operation of the insurer – such as an insurer in run-off or an insurer operating as a going concern. These different scenarios and considerations are discussed in more detail in Guidance 17.6.3 – 17.6.5.

In addition, the supervisor should consider the allowance for management discretion and future action in response to changing circumstances or particular events. In allowing for management discretion, supervisors should only recognise actions which are practical and realistic in the circumstances being considered [11].

[11] The supervisor should carefully consider the appropriateness of allowing for such management discretion in the particular case of the MCR as defined in Standard 17.4.

- the way in which the quality of capital resources is addressed by the supervisor

- the coverage of risks in the determination of technical provisions and regulatory capital requirements and the extent of the sensitivity or stress analysis underpinning those requirements;

- the relation between different levels (for example the extent to which a minimum is set at a conservative level);

- the powers of the supervisor to set and adjust solvency control levels within the regulatory framework;

- the accounting and actuarial framework that applies in the jurisdiction (in terms of the valuation basis and assumptions that may be used and their impact on the values of assets and liabilities that underpin the determination of regulatory capital requirements);

- the comprehensiveness and transparency of disclosure frameworks in the jurisdiction and the ability for markets to exercise sufficient scrutiny and impose market discipline;

- policyholder priority and status under the legal framework relative to other creditors in the jurisdiction;

- overall level of capitalisation in the insurance sector in the jurisdiction;

- overall quality of risk management and governance frameworks in the insurance sector in the jurisdiction;

- the development of capital markets in the jurisdiction and its impact on the ability of insurers to raise capital; and

- the balance to be struck between protecting policyholders and the impact on the effective operation of the insurance sector and considerations around unduly onerous levels and costs of regulatory capital requirements.

While the general considerations in Guidance 17.3.1 to 17.3.7 above on the establishment of solvency control levels apply in a group-wide context as well as a legal entity context, the supervisory actions triggered at group level will be likely to differ from those at legal entity level. As a group is not a legal entity the scope for direct supervisory action in relation to the group as a whole is more limited and action may need to be taken through co-ordinated action at insurance legal entity level.

Nevertheless, group solvency control levels are a useful tool for identifying a weakening of the financial position of a group as a whole or of particular parts of a group, which may, for example, increase contagion risk or impact reputation which may not otherwise be readily identified or assessed by supervisors of individual group entities. The resulting timely identification and mitigation of a weakening of the financial position of a group may thus address a threat to the stability of the group or its component insurance legal entities.

Group-wide solvency control levels may trigger a process of coordination and cooperation between different supervisors of group entities which will facilitate mitigation and resolution of the impact of group-wide stresses on insurance legal entities within a group. Group-wide control levels may also provide a trigger for supervisory dialogue with the group’s management.

- a solvency control level above which the supervisor does not intervene on capital adequacy grounds. This is referred to as the Prescribed Capital Requirement (PCR). The PCR is defined such that assets will exceed technical provisions and other liabilities with a specified level of safety over a defined time horizon.

- a solvency control level at which, if breached, the supervisor would invoke its strongest actions, in the absence of appropriate corrective action by the insurance legal entity. This is referred to as the Minimum Capital Requirement (MCR). The MCR is subject to a minimum bound below which no insurer is regarded to be viable to operate effectively.

A range of different intervention actions should be taken by a supervisor depending on the event or concern that triggers the intervention. Some of these triggers will be linked to the level of an insurer’s capital resources relative to the level at which regulatory capital requirements are set.

In broad terms, the highest regulatory capital requirement, the Prescribed Capital Requirement (PCR), will be set at the level at which the supervisor would not require action to increase the capital resources held or reduce the risks undertaken by the insurer[12]. However if the insurer’s capital resources were to fall below the level at which the PCR is set, the supervisor would require some action by the insurer to either restore capital resources to at least the PCR level or reduce the level of risk undertaken (and hence the required capital level).

[12] Note that this does not preclude the supervisor from intervention or requiring action by the insurer for other reasons, such as weaknesses in the risk management or governance of the insurer. Nor does it preclude the supervisor from intervention when the insurer’s capital resources are currently above the PCR but are expected to fall below that level in the short term. To illustrate, the supervisor may establish a trend test (a time series analysis). A sufficiently adverse trend would require some supervisory action. The trend test would support the objective of early regulatory intervention by considering the speed at which capital deterioration is developing.

The regulatory objective to require that, in adversity, an insurer’s obligations to policyholders will continue to be met as they fall due will be achieved without intervention if technical provisions and other liabilities[13] are expected to remain covered by assets over a defined period, to a specified level of safety. As such, the PCR should be determined at a level such that the insurer is able to absorb the losses from adverse events that may occur over that defined period and the technical provisions remain covered at the end of the period.

[13] To the extent these liabilities are not treated as capital resources.

The Minimum Capital Requirement (MCR) represents the supervisory intervention point at which the supervisor would invoke its strongest actions, if further capital is not made available[14]. Therefore, the main aim of the MCR is to provide the ultimate safety net for the protection of the interests of policyholders.

[14] Note that this does not preclude such actions being taken by the supervisor for other reasons, and even if the MCR is met or exceeded.

These actions could include stopping the activities of the insurer, withdrawal of the insurer’s licence, requiring the insurer to close to new business and run-off the portfolio, transfer its portfolio to another insurer, arrange additional reinsurance, or other specified actions. This position is different from the accounting concept of insolvency as the MCR would be set at a level in excess of that at which the assets of the insurer were still expected to be sufficient to meet the insurer’s obligations to existing policyholders as they fall due. The PCR cannot be less than the MCR, and therefore the MCR may also provide the basis of a lower bound for the PCR, which may be especially appropriate in cases where the PCR is determined on the basis of an insurer’s internal model[15] approved for use in determining regulatory capital requirements by the supervisor.

[15] The term “internal model” refers to “a risk measurement system developed by an insurer to analyse its overall risk position, to quantify risks and to determine the economic capital required to meet those risks”. Internal models may also include partial models which capture a subset of the risks borne by the insurer using an internally developed measurement system which is used in determining the insurer's economic capital. The IAIS is aware that insurers use a variety of terms to describe their risk and capital assessment processes, such as “economic capital model”, “risk-based capital model”, or “business model”. The IAIS considers that such terms could be used interchangeably to describe the processes adopted by insurers in the management of risk and capital within their business on an economic basis. For the purposes of consistency, the term “internal model” is used throughout.

In establishing a minimum bound on the MCR below which no insurer is regarded to be viable to operate effectively, the supervisor may, for example, apply a market-wide nominal floor[16] to the regulatory capital requirements, based on the need for an insurer to operate with a certain minimal critical mass and consideration of what may be required to meet minimum standards of governance and risk management. Such a nominal floor might vary between lines of business or type of insurer and is particularly relevant in the context of a new insurer or line of business.

[16] In this context, a market-wide nominal floor may, for example, be an absolute monetary minimum amount of capital required to be held by an insurer in a jurisdiction.

Regulatory capital requirements may include additional solvency control levels between the level at which the supervisor takes no intervention action from a capital perspective and the strongest intervention point (that is, between the PCR and MCR levels). These control levels may be set at levels that correspond to a range of different intervention actions that may be taken by the supervisor itself or actions which the supervisor would require of the insurer according to the severity or level of concern regarding adequacy of the capital held by the insurer. These additional control levels may be formally established by the supervisor with explicit intervention actions linked to particular control levels. Alternatively, these additional control levels may be structured less formally, with a range of possible intervention actions available to the supervisor depending on the particular circumstances. In either case the possible triggers and range of intervention actions should be appropriately disclosed by the supervisor.

- measures that are intended to enable the supervisor to better assess and/or control the situation, either formally or informally, such as increased supervision activity or reporting, or requiring auditors or actuaries to undertake an independent review or extend the scope of their examinations;

- measures to address capital levels such as requesting capital and business plans for restoration of capital resources to required levels, limitations on redemption or repurchase of equity or other instruments and/or dividend payments;

- measures intended to protect policyholders pending strengthening of the insurer’s capital position, such as restrictions on licences, premium volumes, investments, types of business, acquisitions, reinsurance arrangements;

- measures that strengthen or replace the insurer’s management and/or risk management framework and overall governance processes;

- measures that reduce or mitigate risks (and hence required capital) such as requesting reinsurance, hedging and other mechanisms; and/or

- refusing, or imposing conditions on, applications submitted for regulatory approval such as acquisitions or growth in business.

In the context of group-wide capital adequacy assessment, the regulatory capital requirements establish solvency control levels that are appropriate in the context of the approach to group-wide capital adequacy that is applied.

The supervisor should establish solvency control levels that are appropriate in the context of the approach that is adopted for group-wide capital adequacy assessment. The supervisor should also define the relationship between these solvency control levels and those at legal entity level for insurers that are members of the group. The design of solvency control levels depends on a number of factors. These include the supervisory perspective, ie the relative weight placed on group-wide supervision and legal entity supervision, and the organisational perspective, ie the extent to which a group is considered as a set of interdependent entities or a single integrated entity. The solvency control levels are likely to vary according to the particular group and the supervisors involved. (see Figure 17.1). The establishment of group-wide solvency control levels should be such as to enhance the overall supervision of the insurers in the group.

Having group-wide solvency control levels does not necessarily mean establishing a single regulatory capital requirement at group level. For example, under a legal entity approach consideration of the set of capital requirements for individual entities (and interrelationships between them) may enable appropriate decisions to be taken about supervisory intervention on a group-wide basis. However, this requires the approach to be sufficiently well developed for group risks to be taken into account on a complete and consistent basis in the capital adequacy assessment of insurance legal entities in a group. To achieve consistency for insurance legal entity assessments, it may be necessary to adjust the capital requirements used for insurance legal entities so they are suitable for group-wide assessment.

One approach may be to establish a single group-wide PCR or a consistent set of PCRs for insurance legal entities that are members of the group which, if met, would mean that no supervisory intervention at group level for capital reasons would be deemed necessary or appropriate. Such an approach may assist, for example, in achieving consistency of approach towards similar organisations with a branch structure and different group structures eg following a change in structure of a group. Where a single group-wide PCR is determined, it may differ from the sum of insurance legal entity PCRs because of group factors including group diversification effects, group risk concentrations and intra-group transactions. Similarly, where group-wide capital adequacy assessment involves the determination of a set of PCRs for the insurance legal entities in an insurance group, these may differ from the insurance legal entity PCRs if group factors are reflected differently in the group capital assessment process. Differences in the level of safety established by different jurisdictions in which the group operates should be considered when establishing group-wide PCR(s).

The establishment of a single group-wide MCR might also be considered and may, for example, trigger supervisory intervention to restructure the control and/or capital of the group. A possible advantage of this approach is that it may encourage a group solution where an individual insurer is in financial difficulty and capital is sufficiently fungible and assets are transferable around the group. Alternatively, the protection provided by the supervisory power to intervene at individual entity level on breach of an insurance legal entity MCR may be regarded as sufficient.

The solvency control levels adopted in the context of group-wide capital adequacy assessment should be designed so that together with the solvency control levels at insurance legal entity level they represent a consistent ladder of supervisory intervention. For example, a group-wide PCR should trigger supervisory intervention before a group-wide MCR because the latter may invoke the supervisor’s strongest actions. Also, if a single group-wide PCR is used it may be appropriate for it to have a floor equal to the sum of the legal entity MCRs of the individual entities in the insurance group. Otherwise, no supervisory intervention into the operation of the group would be required even though at least one of its member insurers had breached its MCR.

Supervisory intervention triggered by group-wide solvency control levels should take the form of coordinated action by relevant group supervisors. This may, for example, involve increasing capital at holding company level or strategically reducing the risk profile or increasing capital in insurance legal entities within the group. Such supervisory action may be exercised via the insurance legal entities within a group and, where insurance holding companies are authorised, via those holding companies. Supervisory action in response to breaches of group-wide solvency control levels should not alter the existing division of statutory responsibilities of the supervisors responsible for authorising and supervising each individual insurance legal entity.

The regulatory capital requirements are established in an open and transparent process, and the objectives of the regulatory capital requirements and the bases on which they are determined are explicit. In determining regulatory capital requirements, the supervisor allows a set of standardised and, if appropriate, other approved more tailored approaches such as the use of (partial or full) internal models.

Transparency as to the regulatory capital requirements that apply is required to facilitate effective solvency assessment and supports its enhancement, comparability and convergence internationally.

The supervisor may develop separate approaches for the determination of different regulatory capital requirements, in particular for the determination of the MCR and the PCR. For example, the PCR and MCR may be determined by two separate methods, or the same methods and approaches may be used but with two different levels of safety specified. In the latter case, for example, the MCR may be defined as a simple proportion of the PCR, or the MCR may be determined on different specified target criteria to those specified for the PCR.

The PCR would generally be determined on a going concern basis, ie in the context of the insurer continuing its operations. On a going concern basis, an insurer would be expected to continue to take on new risks during the established time horizon. Therefore, in establishing the regulatory capital level to provide an acceptable level of solvency, the potential growth in an insurer’s portfolio should be considered.

Capital should also be capable of protecting policyholders if the insurer were to close to new business. Generally, the determination of capital on a going concern basis would not be expected to be less than would be required if it is assumed that the insurer were to close to new business. However, this may not be true in all cases, since some assets may lose some or all of their value in the event of a winding-up or run-off, for example, because of a forced sale. Similarly, some liabilities may actually have an increased value if the business does not continue (eg claims handling expenses).

Usually the MCR would be constructed taking into consideration the possibility of closure to new business. It is, however, relevant to also consider the going concern scenario in the context of establishing the level of the MCR, as an insurer may continue to take on new risks up until the point at which MCR intervention is ultimately triggered. The supervisor should consider the appropriate relationship between the PCR and MCR, establishing a sufficient buffer between these two levels (including consideration of the basis on which the MCR is generated) within an appropriate continuum of solvency control levels, having regard for the different situations of business operation and other relevant considerations.

It should be emphasised that meeting the regulatory capital requirements should not be taken to imply that further financial injections will not be necessary under any circumstances in future.

Regulatory capital requirements may be determined using a range of approaches, such as standard formulae, or other approaches, more tailored to the individual insurer (such as partial or full internal models), which are subject to approval by the relevant supervisors.[17] Regardless of the approach used, the principles and concepts that underpin the objectives for regulatory capital requirements described in this ICP apply and should be applied consistently by the supervisor to the various approaches. The approach adopted for determining regulatory capital requirements should take account of the nature and materiality of the risks insurers face generally and, to the extent practicable, should also reflect the nature, scale and complexity of the risks of the particular insurer.

[17] A more tailored approach which is not an internal model might include, for example, approved variations in factors contained in a standard formula or prescribed scenario tests which are appropriate for a particular insurer or group of insurers.

Standardised approaches, in particular, should be designed to deliver capital requirements which reasonably reflect the overall risk to which insurers are exposed, while not being unduly complex. Standardised approaches may differ in level of complexity depending on the risks covered and the extent to which they are mitigated or may differ in application based on classes of business (eg life and non-life). Standardised approaches should be appropriate to the nature, scale and complexity of the risks that insurers face and should include approaches that are feasible in practice for insurers of all types including small and medium sized insurers and captives taking into account the technical capacity that insurers need to manage their businesses effectively.

By its very nature a standardised approach may not be able to fully and appropriately reflect the risk profile of each individual insurer. Therefore, where appropriate, a supervisor should allow the use of more tailored approaches subject to approval. In particular, where an insurer has an internal model (or partial internal model) that appropriately reflects its risks and is integrated into its risk management and reporting, the supervisor should allow the use of such a model to determine more tailored regulatory capital requirements, where appropriate[18]. The use of the internal model for this purpose would be subject to prior approval by the supervisor based on a transparent set of criteria and would need to be evaluated at regular intervals. In particular, the supervisor would need to be satisfied that the insurer’s internal model is, and remains, appropriately calibrated relative to the target criteria established by the supervisor (see Guidance 17.12.1 to 17.12.18).

[18] It is noted that the capacity for a supervisor to allow the use of internal models will need to take account of the sufficiency of resources available to the supervisor.

The supervisor should also be clear on whether an internal model may be used for the determination of the MCR. In this regard, the supervisor should take into account the main objective of the MCR (ie to provide the ultimate safety net for the protection of policyholders) and the ability of the MCR to be defined in a sufficiently objective and appropriate manner to be enforceable (refer to Guidance 17.3.4).

The supervisor addresses all relevant and material categories of risk in insurers and is explicit as to where risks are addressed, whether solely in technical provisions, solely in regulatory capital requirements or if addressed in both, as to the extent to which the risks are addressed in each. The supervisor is also explicit as to how risks and their aggregation are reflected in regulatory capital requirements.

The supervisor should address all relevant and material categories of risk – including at least underwriting risk, credit risk, market risk, operational risk and liquidity risk. This should include any significant risk concentrations, for example, to economic risk factors, market sectors or individual counterparties, taking into account both direct and indirect exposures and the potential for exposures in related areas to become more correlated under stressed circumstances.

The assessment of the overall risk that an insurer is exposed to should address the dependencies and interrelationships between risk categories (for example, between underwriting risk and market risk) as well as within a risk category (for example, between equity risk and interest rate risk). This should include an assessment of potential reinforcing effects between different risk types as well as potential “second order effects”, ie indirect effects to an insurer’s exposure caused by an adverse event or a change in economic or financial market conditions.[19] It should also consider that dependencies between different risks may vary as general market conditions change and may significantly increase during periods of stress or when extreme events occur. “Wrong way risk”, which is defined as the risk that occurs when exposure to counterparties, such as financial guarantors, is adversely correlated to the credit quality of those counterparties, should also be considered as a potential source of significant loss eg in connection with derivative transactions. Where the determination of an overall capital requirement takes into account diversification effects between different risk types, the insurer should be able to explain the allowance for these effects and ensure that it considers how dependencies may increase under stressed circumstances.

[19] For example, a change in the market level of interest rates could trigger an increase of lapse rates on insurance policies.

Any allowance for reinsurance in determining regulatory capital requirements should consider the possibility of breakdown in the effectiveness of the risk transfer and the security of the reinsurance counterparty and any measures used to reduce the reinsurance counterparty exposure. Similar considerations would also apply for other risk mitigants, for example derivatives.

The supervisor should be explicit as to where risks are addressed, whether solely in technical provisions, solely in regulatory capital requirements or if addressed in both, as to the extent to which the risks are addressed in each. The solvency requirements should also clearly articulate how risks are reflected in regulatory capital requirements, specifying and publishing the level of safety to be applied in determining regulatory capital requirements, including the established target criteria (refer to Standard 17.8).

The IAIS recognises that some risks, such as strategic risk, reputational risk, liquidity risk and operational risk, are less readily quantifiable than the other main categories of risks. Operational risk, for example, is diverse in its composition and depends on the quality of systems and controls in place. The measurement of operational risk, in particular, may suffer from a lack of sufficiently uniform and robust data and well developed valuation methods. Jurisdictions may choose to base regulatory capital requirements for these less readily quantifiable risks on some simple proxies for risk exposure and/or stress and scenario testing. For particular risks (such as liquidity risk), holding additional capital may not be the most appropriate risk mitigant and it may be more appropriate for the supervisor to require the insurer to control these risks via exposure limits and/or qualitative requirements such as additional systems and controls.

However, the IAIS envisages that the ability to quantify some risks (such as operational risk) will improve over time as more data become available or improved valuation methods and modelling approaches are developed. Further, although it may be difficult to quantify risks, it is important that an insurer nevertheless addresses all material risks in its own risk and solvency assessment.

The supervisor sets appropriate target criteria for the calculation of regulatory capital requirements, which underlie the calibration of a standardised approach. Where the supervisor allows the use of approved more tailored approaches such as internal models for the purpose of determining regulatory capital requirements, the target criteria underlying the calibration of the standardised approach are also used by those approaches for that purpose to require broad consistency among all insurers within the jurisdiction.

The level at which regulatory capital requirements are set will reflect the risk tolerance of the supervisor. Reflecting the IAIS’s principles-based approach, this ICP does not prescribe any specific methods for determining regulatory capital requirements. However, the IAIS’s view is that it is important that individual jurisdictions set appropriate target criteria (such as risk measures, confidence levels or time horizons) for their regulatory capital requirements. Further, each jurisdiction should outline clear principles for the key concepts for determining regulatory capital requirements, considering the factors that a supervisor should take into account in determining the relevant parameters as outlined in this ICP.

Where a supervisor allows the use of other more tailored approaches to determine regulatory capital requirements, the target criteria established should be applied consistently to those approaches. In particular, where a supervisor allows the use of internal models for the determination of regulatory capital requirements, the supervisor should apply the target criteria in approving the use of an internal model by an insurer for that purpose. This should achieve broad consistency among all insurers and a similar level of protection for all policyholders, within the jurisdiction.

With regards to the choice of the risk measure and confidence level to which regulatory capital requirements are calibrated, the IAIS notes that some supervisors have set a confidence level for regulatory purposes which is comparable with a minimum investment grade level. Some examples have included a 99.5% VaR calibrated confidence level over a one year timeframe,[20] 99% TVaR over one year and 95% TVaR over the term of the policy obligations.

[20] This is the level expected in Australia for those insurers that seek approval to use an internal model to determine their MCR. It is also the level used for the calculation of the risk-based Solvency Capital Requirement under the European Solvency II regime.

In regards to the choice of an appropriate time horizon, the determination and calibration of the regulatory capital requirements needs to be based on a more precise analysis, distinguishing between:

- the period over which a shock is applied to a risk – the “shock period”; and

- the period over which the shock that is applied to a risk will impact the insurer – the “effect horizon”.

For example, a one-off shift in the interest rate term structure during a shock period of one year has consequences for the discounting of the cash flows over the full term of the policy obligations (the effect horizon). A judicial opinion (eg on an appropriate level of compensation) in one year (the shock period) may have permanent consequences for the value of claims and hence will change the projected cash flows to be considered over the full term of the policy obligations (the effect horizon).

The impact on cash flows of each stress that is assumed to occur during the shock period will need to be calculated over the period for which the shock will affect the relevant cash flows (the effect horizon). In many cases this will be the full term of the insurance obligations. In some cases, realistic allowance for offsetting reductions in discretionary benefits to policyholders or other offsetting management actions may be considered, where they could and would be made and would be effective in reducing policy obligations or in reducing risks in the circumstances of the stress. In essence, at the end of the shock period, capital has to be sufficient so that assets cover the technical provisions (and other liabilities) re-determined at the end of the shock period. The re-determination of the technical provisions would allow for the impact of the shock on the technical provisions over the full time horizon of the policy obligations.

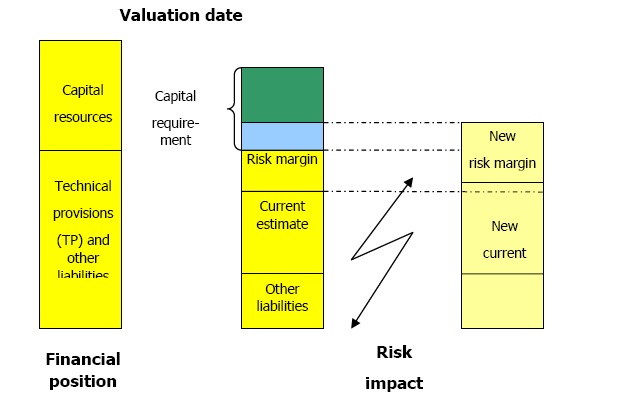

Figure 17.3: Illustration of determination of regulatory capital requirements

For the determination of the technical provisions, an insurer is expected to consider the uncertainty attached to the policy obligations, that is, the likely (or expected) variation of future experience from what is assumed in determining the current estimate, over the full period of the policy obligations. As indicated above, regulatory capital requirements should be calibrated such that assets exceed the technical provisions (and other liabilities) over a defined shock period with an appropriately high degree of safety. That is, the regulatory capital requirements should be set such that the insurer’s capital resources can withstand a range of predefined shocks or stress scenarios that are assumed to occur during that shock period (and which lead to significant unexpected losses over and above the expected losses that are captured in the technical provisions).

The risk of measurement error inherent in any approach used to determine capital requirements should be considered. This is especially important where there is a lack of sufficient statistical data or market information to assess the tail of the underlying risk distribution. To mitigate model error, quantitative risk calculations should be blended with qualitative assessments, and, where practicable, multiple risk measurement tools should be used. To help assess the economic appropriateness of risk-based capital requirements, information should be sought on the nature, degree and sources of the uncertainty surrounding the determination of capital requirements in relation to the established target criteria.

The degree of measurement error inherent, in particular, in a standardised approach depends on the degree of sophistication and granularity of the methodology used. A more sophisticated standardised approach has the potential to be aligned more closely to the true distribution of risks across insurers. However, increasing the sophistication of the standardised approach is likely to imply higher compliance costs for insurers and more intensive use of supervisory resources (for example, in validating the calculations). The calibration of the standardised approach therefore needs to balance the trade-off between risk-sensitivity and implementation costs.

When applying risk-based regulatory capital requirements, there is a risk that an economic downturn will trigger supervisory interventions that exacerbate the economic crises, thus leading to an adverse “procyclical” effect. For example, a severe downturn in share markets may result in a depletion of the capital resources of a major proportion of insurers. This in turn may force insurers to sell shares and to invest in less risky assets in order to decrease their regulatory capital requirements. A simultaneous massive selling of shares by insurers could, however, put further pressure on the share markets, thus leading to a further drop in share prices and to a worsening of the economic crises.

However, the system of solvency control levels required enables supervisors to introduce a more principles-based choice of supervisory interventions in cases where there may be a violation of the PCR control level and this can assist in avoiding exacerbation of procyclicality effects: supervisory intervention is able to be targeted and more flexible in the context of an overall economic downturn so as to avoid measures that may have adverse macroeconomic effects.

It could be contemplated whether further explicit procyclicality-dampening measures would be needed. This may include allowing a longer period for corrective measures or allowance for the calibration of the regulatory capital requirements to reflect procyclicality dampening measures. Overall, when such dampening measures are applied, an appropriate balance needs to be achieved to preserve the risk sensitivity of the regulatory capital requirements.

In considering the impacts of procyclicality, the influence of external factors (for example, the influence of credit rating agencies) should be given due regard. The impacts of procyclicality also heighten the need for supervisory cooperation and communication.

Approaches to determining group-wide regulatory capital requirements will depend on the overall approach taken to group-wide capital adequacy assessment. Where a group level approach is used, either the group’s consolidated accounts may be taken as a basis for calculating group-wide capital requirements or the requirements of each insurance legal entity may be aggregated or a mixture of these methods may be used. For example, if a different treatment is required for a particular entity (for example, an entity located in a different jurisdiction) it might be disaggregated from the consolidated accounts and then included in an appropriate way using a deduction and aggregation approach.

Where consolidated accounts are used, the requirements of the jurisdiction in which the ultimate parent of the group is located would normally be applied, consideration should also be given to the scope of the consolidated accounts used for accounting purposes as compared to the consolidated balance sheet used as a basis for group-wide capital adequacy assessment to require, for example, identification and appropriate treatment of non-insurance group entities.

Where the aggregation method is used (as described in Guidance 17.1.13), or where a legal entity focus is adopted (as described in Guidance 17.1.14), consideration should be given as to whether local capital requirements can be used for insurance legal entities within the group which are located in other jurisdictions or whether capital requirements should be recalculated according to the requirements of the jurisdiction in which the ultimate parent of the group is located.

There are a number of group-specific factors which should be taken into account in determining group-wide capital requirements including diversification of risk across group entities, intra-group transactions, risks arising from non-insurance group entities, treatment of group entities located in other jurisdictions and treatment of partially-owned entities and minority interests. Particular concerns may arise from a continuous sequence of internal financing within the group, or closed loops in the financing scheme of the group.

Group specific risks posed by each group entity to insurance members of the group and to the group as a whole are a key factor in an overall assessment of group-wide capital adequacy. Such risks are typically difficult to measure and mitigate and include notably contagion risk (financial, reputational, legal), concentration risk, complexity risk and operational/organisational risks. As groups can differ significantly it may not be possible to address these risks adequately using a standardised approach for capital requirements. It may therefore be necessary to address group specific risks through the use of more tailored approaches to capital requirements including the use of (partial or full) internal models. Alternatively, supervisors may vary the standardised regulatory capital requirement so that group-specific risks are adequately provided for in the insurance legal entity and/or group capital adequacy assessment.[21]

[21] See Standard 17.9.

Group specific risks should be addressed from both an insurance legal entity perspective and group-wide perspective ensuring that adequate allowance is made. Consideration should be given to the potential for duplication or gaps between insurance legal entity and group-wide approaches.

In the context of a group-wide solvency assessment, there should also be consideration of dependencies and interrelations of risks across different members in the group. However, it does not follow that where diversification effects exist these should be recognised automatically in an assessment of group-wide capital adequacy. It may, for example, be appropriate to limit the extent to which group diversification effects are taken into account for the following reasons:

- Diversification may be difficult to measure at any time and in particular in times of stress. Appropriate aggregation of risks is critical to the proper evaluation of such benefits for solvency purposes.

- There may be constraints on the transfer of diversification benefits across group entities and jurisdictions because of a lack of fungibility of capital or transferability of assets.

- Diversification may be offset by concentration/aggregation effects (if this is not separately addressed in the assessment of group capital).

An assessment of group diversification benefits is necessary under whichever approach used to assess group-wide capital adequacy. Under a legal entity approach, recognition of diversification benefits will require consideration of the diversification between the business of an insurance legal entity and other entities within the group in which it participates and of intra-group transactions. Under an approach with a consolidation focus which uses the consolidated accounts method, some diversification benefits will be recognised automatically at the level of the consolidated group. In this case, supervisors will need to consider whether it is prudent to recognise such benefits or whether an adjustment should be made in respect of potential restrictions on the transferability or sustainability under stress of surplus resources created by group diversification benefits.

Intra-group transactions may result in complex and/or opaque intra-group relationships which give rise to increased risks at both insurance legal entity and group level. In a group-wide context, credit for risk mitigation should only be recognised in group capital requirements to the extent that risk is transferred outside the group. For example, the transfer of risk to a captive reinsurer or to an intra-group insurance special purpose entity should not result in a reduction of overall group capital requirements.

In addition to insurance legal entities, an insurance group may include a range of different types of non-insurance legal entity, either subject to no financial regulation (non-regulated entities) or regulated under other financial sector regulation. The impact of all such entities should be taken into account in the overall assessment of group-wide solvency but the extent to which they can be captured in a group-wide capital adequacy measure as such will vary according to the type of non-insurance legal entity, the degree of control/influence on that entity and the approach taken to group-wide supervision.

Risks from non-regulated entities are typically difficult to measure and mitigate. Supervisors may not have direct access to information on such entities but it is important that supervisors are able to assess the risks they pose in order to apply appropriate mitigation measures. Measures taken to address risks from non-regulated entities do not imply active supervision of such entities.

There are different approaches to addressing risks stemming from non-regulated entities such as capital measures, non-capital measures or a combination thereof.

One approach may be to increase capital requirements in order that the group holds sufficient capital. If the activities of the non-regulated entities have similar risk characteristics to insurance activities (eg certain credit enhancement mechanisms as compared to traditional bond insurance) it may be possible to calculate an equivalent capital charge. Another approach might be to deduct the value of holdings in non-regulated entities from the capital resources of the insurance legal entities in the group, but this on its own may not be sufficient to cover the risks involved.

Non-capital measures may include, for example, limits on exposures and requirements on risk management and governance applied to insurance legal entities with respect to non-regulated entities within the group.

Group-wide capital adequacy assessments should, to the extent possible, be based on consistent application of ICPs across jurisdictions. In addition, consideration should be given to the capital adequacy and transferability of assets in entities located in different jurisdictions.

An assessment of group-wide capital adequacy should include an appropriate treatment of partially-owned or controlled group entities and minority interests. Such treatment should take into account the nature of the relationships of the partially-owned entities within the group and the risks and opportunities they bring to the group. The accounting treatment may provide a starting point. Consideration should be given to the availability of any minority interest’s share in the net equity in excess of regulatory capital requirements of a partially-owned entity.

Any variations to the regulatory capital requirement imposed by the supervisor are made within a transparent framework, are appropriate to the nature, scale and complexity according to the target criteria and are only expected to be required in limited circumstances.

As has already been noted, a standardised approach, by its very nature, may not be able to fully and appropriately reflect the risk profile of each individual insurer. In cases where the standardised approach established for determining regulatory capital requirements is materially inappropriate for the risk profile of the insurer, the supervisor should have the flexibility to increase the regulatory capital requirement calculated by the standard approach. For example, some insurers using the standard formula may warrant a higher PCR and/or group-wide regulatory capital requirement if they are undertaking higher risks, such as new products where credible experience is not available to establish technical provisions, or if they are undertaking significant risks that are not specifically covered by the regulatory capital requirements.

Similarly, in some circumstances when an approved more tailored approach is used for regulatory capital purposes, it may be appropriate for the supervisor to have some flexibility to increase the capital requirement calculated using that approach. In particular, where an internal model or partial internal model is used for regulatory capital purposes, the supervisor may increase the capital requirement where it considers the internal model does not adequately capture certain risks, until the identified weaknesses have been addressed. This may arise, for example, even though the model has been approved where there has been a change in the business of the insurer and there has been insufficient time to fully reflect this change in the model and for a new model to be approved by the supervisor.

In addition, supervisory requirements may be designed to allow the supervisor to decrease the regulatory capital requirement for an individual insurer where the standardised requirement materially overestimates the capital required according to the target criteria. However, such an approach may require a more intensive use of supervisory resources due to requests from insurers for consideration of a decrease in their regulatory capital requirement. Therefore, the IAIS appreciates that not all jurisdictions may wish to include such an option for their supervisor. Further, this reinforces the need for such variations in regulatory capital requirements to only be expected to be made in limited circumstances.

Any variations made by the supervisor to the regulatory capital requirement calculated by the insurer should be made in a transparent framework and be appropriate to the nature, scale and complexity in terms of the target criteria. The supervisor may, for example, develop criteria to be applied in determining such variations and appropriate discussions between the supervisor and the insurer may occur. Variations in regulatory capital requirements following supervisory review from those calculated using standardised approaches or approved more tailored approaches should be expected to be made only in limited circumstances.

In undertaking its ORSA, the insurer considers the extent to which the regulatory capital requirements (in particular, any standardised formula) adequately reflect its particular risk profile. In this regard, the ORSA undertaken by an insurer can be a useful source of information to the supervisor in reviewing the adequacy of the regulatory capital requirements of the insurer and in assessing the need for variation in those requirements.

The supervisor defines the approach to determining the capital resources eligible to meet regulatory capital requirements and their value, consistent with a total balance sheet approach for solvency assessment and having regard to the quality and suitability of capital elements.

The following outlines a number of approaches a supervisor could use for the determination of capital resources in line with this requirement. The determination of capital resources would generally require the following steps:

- the amount of capital resources potentially available for solvency purposes is identified (see Guidance 17.10.3 – 17.10.21);

- an assessment of the quality and suitability of the capital instruments comprising the total amount of capital resources identified is then carried out (see Guidance 17.11.1 – 17.11.29); and

- on the basis of this assessment, the final capital resources eligible to meet regulatory capital requirements and their value are determined (see Guidance 17.11.30 – 17.11.44).

In addition, the insurer is required to carry out its own assessment of its capital resources to meet regulatory capital requirements and any additional capital needs (see Standard 16.14).

The IAIS supports the use of a total balance sheet approach in the assessment of solvency to recognise the interdependence between assets, liabilities, regulatory capital requirements and capital resources so that risks are appropriately recognised.

Such an approach requires that the determination of available and required capital is based on consistent assumptions for the recognition and valuation of assets and liabilities for solvency purposes.

From a regulatory perspective, the purpose of regulatory capital requirements is to require that, in adversity, an insurer’s obligations to policyholders will continue to be met as they fall due. This aim will be achieved if technical provisions and other liabilities are expected to remain covered by assets over a defined period, to a specified level of safety[22].

[22] Refer to Guidance 17.3.1 – 17.9.5.

- the extent to which certain liabilities other than technical provisions may be treated as capital for solvency purposes (Guidance 17.10.8 – 17.10.10);

- whether contingent assets could be included (Guidance 17.10.11);

- the treatment of assets which may not be fully realisable in the normal course of business or under a wind-up scenario (Guidance 17.10.12 – 17.10.19); and

- reconciliation of such a “top down” approach to determining capital resources with a “bottom up” approach which sums up individual items of capital to derive the overall amount of capital resources (Guidance 17.10.20).

Liabilities include technical provisions and other liabilities. Certain items such as other liabilities in the balance sheet may be treated as capital resources for solvency purposes.

For example, perpetual subordinated debt, although usually classified as a liability under the relevant accounting standards, could be classified as a capital resource for solvency purposes.[23] This is because of its availability to act as a buffer to reduce the loss to policyholders and senior creditors through subordination in the event of insolvency. More generally, subordinated debt instruments (whether perpetual or not) may be treated as capital resources for solvency purposes if they satisfy the criteria established by the supervisor. Other liabilities that are not subordinated would not be considered as part of the capital resources; examples include liabilities such as deferred tax liabilities and pension liabilities.

[23] However, adequate recognition should be given to contractual features of the debt such as embedded options which may change its loss absorbency.

It may, therefore, be appropriate to exclude some elements of funding from liabilities and so include them in capital to the extent appropriate. This would be appropriate if these elements have characteristics which protect policyholders by meeting one or both of the objectives set out in Guidance 17.2.6 above.

It may be appropriate to include contingent elements which are not considered as assets under the relevant accounting standards, where the likelihood of payment if needed is sufficiently high according to criteria specified by the supervisor. Such contingent capital may include, for example, letters of credit, members’ calls by a mutual insurer or the unpaid element of partly paid capital and may be subject to prior approval by the supervisor.

Supervisors should consider that, for certain assets in the balance sheet, the realisable value under a wind-up scenario may become significantly lower than the economic value which is attributable under going concern conditions. Similarly, even under normal business conditions, some assets may not be realisable at full economic value, or at any value, at the time they are needed. This may render such assets unsuitable for inclusion at their full economic value for the purpose of meeting required capital.[24]

[24] In particular, supervisors should consider the value of contingent assets for solvency purposes taking into account the criteria set out in Guidance 17.11.21.

- own shares directly held by the insurer: the insurer has bought and is holding its own shares thereby reducing the amount of capital available to absorb losses under going concern or in a wind-up scenario;

- intangible assets: their realisable value may be uncertain even during normal business conditions and may have no significant marketable value in run-off or winding-up; Goodwill is a common example;

- future income tax credits: such credits may only be realisable if there are future taxable profits, which is improbable in the event of insolvency or winding-up;

- implicit accounting assets: under some accounting models, certain items regarding future income are included, implicitly or explicitly, as asset values. In the event of run-off or winding-up, such future income may be reduced;

- investments[25] in other insurers or financial institutions: such investments may have uncertain realisable value because of contagion risk between entities; also there is the risk of “double gearing” where such investments lead to a recognition of the same amount of available capital resources in several financial entities; and

- company-related assets: certain assets carried in the accounting statements of the insurer could lose some of their value in the event of run-off or winding-up, for example physical assets used by the insurer in conducting its business which may reduce in value if there is a need for the forced sale of such assets. Also, certain assets may not be fully accessible to the insurer eg surplus in a corporate pension arrangement.

- directly, by not admitting a portion of the economic value of the asset for solvency purposes (deduction approach); or

- indirectly, through an addition to regulatory capital requirements (capital charge approach).

Under the deduction approach, the economic value of the asset is reduced for solvency purposes. This results in capital resources being reduced by the same amount. The partial (or full) exclusion of such an asset may occur for a variety of reasons, for example, to reflect an expectation that it would have only limited value in the event of insolvency or winding-up to absorb losses. No further adjustment would normally be needed in the determination of regulatory capital requirements for the risk of holding such assets.

As outlined above, an application of the deduction approach would lead to a reduction in the amount of available capital resources, whereas an application of the capital charge approach would result in an increase in regulatory capital requirements. Provided the two approaches are based on a consistent economic assessment of the risk associated with the relevant assets, they would be expected to produce broadly similar results regarding the overall assessment of the solvency position of the insurer.

For some asset classes, it may be difficult to determine a sufficiently reliable economic value or to assess the associated risks. Such difficulties may also arise where there is a high concentration of exposure to a particular asset or type of assets or to a particular counterparty or group of counterparties.

A supervisor should choose the approach which is best suited to the organisation and sophistication of the insurance sector and the nature of the asset class and asset exposure considered. It may also combine different approaches for different classes of assets. Whatever approach is chosen, it should be transparent and consistently applied. It is also important that any material double counting or omission of risks under the calculations for determining the amounts of required and available regulatory capital is avoided.

The approach to determining available capital resources as broadly the amount of assets over liabilities (with the potential adjustments as discussed above) may be described as a “top-down” approach – ie starting with the high level capital as reported in the balance sheet and adjusting it in the context of the relevant solvency control level. An alternative approach which is also applied in practice is to sum up the amounts of particular items of capital which are specified as being acceptable. Such a “bottom-up” approach should be reconcilable to the “top-down” approach on the basis that the allowable capital items under the “bottom-up approach” should ordinarily include all items which contribute to the excess of assets over liabilities in the balance sheet, with the addition or exclusion of items as per the discussion in Guidance 17.10.8 – 17.10.19.

- the way in which the quality of capital resources is addressed by the supervisor, including whether or not quantitative requirements are applied to the composition of capital resources and/or whether or not a categorisation or continuum- based approach is used;

- the coverage of risks in the determination of technical provisions and regulatory capital requirements;

- the assumptions in the valuation of assets and liabilities (including technical provisions) and the determination of regulatory capital requirements, eg going concern basis or wind-up basis, before tax or after tax, etc;

- policyholder priority and status under the legal framework relative to other creditors in the jurisdiction;